Return to MODULE PAGE

Searle and the Chinese Room Argument

David Leech Anderson: Text Author, Storyboards

Robert Stufflebeam: Animations, Storyboards

Kari Cox: Animations

PART ONE: The Argument

Is it possible for a machine to be intelligent? to understand a language? If it is to understand a language, our “intelligent machine” must be able to grasp the meanings of words and sentences (for example, the sentence: “It will rain on Friday.”) And if it can do that, then it can have beliefs (“I believe that it will rain on Friday"). And if it can have beliefs then possibly it can have other mental states like hopes (“I hope that it will rain on Friday”) and fears (“I fear that it will rain on Friday”). But what is required to grasp the meanings of words?

Beliefs, hopes, fears, and even pains are all mental states. A thing that can have such mental states is said to have a “mind.” So what we are really asking is: “Is it possible for a machine to have a mind?” While there are many films that show us robots that behave as if they have minds, that is an illusion fashioned by Hollywood. The illusion is accomplished either by human beings who do have minds pretending to be robots or by machines that don't have minds being made (through special effects) to behave as if they do. We want to know whether a machine might one day genuinely have a mind.

Whether a machine could have a mind depends, of course, on what a "mind" is. Through the ages, a variety of different theories have been advanced which claim to explain the essential nature of "minds." One theory which has gone the furthest to encourage people to believe that a machine could have a mind is the theory known as "functionalism." [A general introduction to Functionalism is available here.] According to this theory, a mental state (like my belief that "It will rain today") is characterized by the function or purpose that it services within the life of the individual. This is often described as its "causal role." There are several different varieties of functionalism, but the most influential is computational functionalism which is sometimes called the "computational theory of mind." Mental states, on this account, are analogous to the software states of a computer. Your brain is the hardware and your mind is the software. If computational functionalism is true, then certainly it is possible for a machine to have mental states. All that is required is that the machine run the right kind of software.

Functionalism is one of the influences that has encouraged people to believe in the possibility of intelligent machines. Another such influence is the conviction that the only fair measure of intelligence (the only reasonable criteria) is a performance test. If something can behave as intelligently as a human being, then it should be credited with possessing that property. ("If it walks like a duck and talks like a duck, then it’s a duck.") It wouldn't be fair to deny it intelligence just because its body is made of metal instead of organic materials, would it? In the past some groups of people have claimed that other groups are of lesser intelligence and are less worthy of respect simply because of their ancestry, their skin color, or their gender. We should not want to make the same mistake with machines, if indeed the only relevant difference is the "stuff" out which they are made.

Alan Turing was the first person to offer a test for machine intelligence: The Turing Test. While Turing himself denied that his test could determine whether a machine could actually "think" or have a "mind" (Turing thought these questions were too vague to answer), he did believe that his was the only concrete way to ask a meaningful version of that question. His new question was something like: "Could a machine carry on a conversation sufficienty well to fool humans into thinking that it was human?" This is a practical question for which a test can be designed. While the Turing Test is controversial, there are many who find it a reasonable test for intelligence and for language understanding.

John Searle is not among this group. He rejects functionalism and does not believe that the Turing Test is a reliable test for intelligence. In fact, he believes that he has an argument that shows that no classical artificial intelligence program [see Computer Types: Classical vs. Non-classical] running on a digital computer will give a machine the capacity to understand a language. He calls his argument the "Chinese Room Argument." [NOTE: Searle actually believes that his argument works against "non-classical" computers as well, but it is best to start with the digital computers with which we are all most familiar.]

The Chinese Room

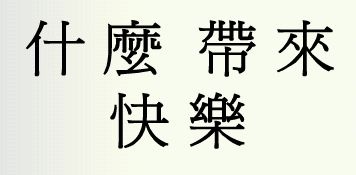

Searle asks you to imagine the following scenario** : There is a room. Sometimes people come to the room with a piece of paper which they slip into the room through a slot. Then they wait a while until the same piece of paper comes back out of a room through a second slot. You soon discover that the people slipping the paper into the room are native Chinese speakers who are sending questions into the room. Let's imagine that they have written the following question:

|

Fig 1: This

question in Chinese means " What

brings happiness?" |

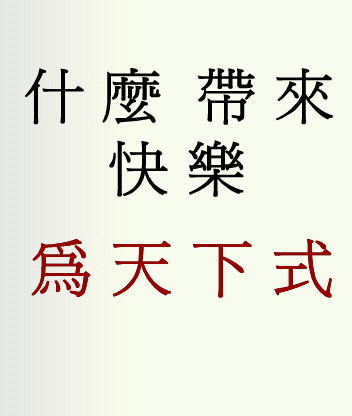

When the paper is later passed out of the room, the Chinese speakers discover that an answer has been written below the question. The answer is also in Chinese and the native speakers determine that it is, in fact, a wise answer to the question. (We made up the question, but we borrowed a line from The Tao Te Ching by Lao Tsu hoping for a "wise" answer.)

|

| Fig 2. The answer to the question is highlighted in red. This sentence is from Lao-Tzu's Tao Te Ching. It means "Be the stream of the universe." |

When the Chinese speakers receive intelligent answers to their questions, they reasonably conclude that there is an intelligent person inside the room who understands Chinese. But, in this thought experiment we are to imagine that the only person inside the room understands no Chinese and speaks only English. For the sake of discussion, we will assume it is Searle himself; you can assume (if you like) that it is you in the room. The room is full of books. Messages are passed into the room with symbols written on them. Searle's job is to look through the books until he finds the string of symbols that look exactly like the ones written on the piece of paper. When he finds that string of symbols, the book will tell him (in English) what new string of symbols he is to write on the bottom of the page, below the first string of symbols.

| ** NOTE: We have modified Searle's story slightly, leaving out some unnecessary details and adding a few embellishments to help clarify the main points. (For example, we have introduced a specific Chinese question and answer which Searle did not.) We recommend that you read the original article to get Searle's version of the story. |

|

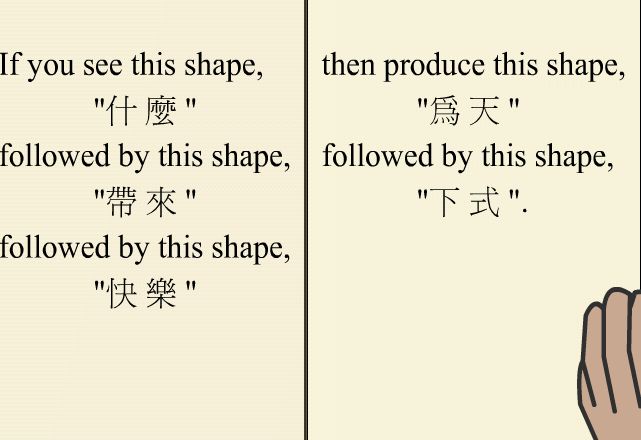

Fig. 3: This is a page (as we imagine it) from one of the volumes in Searle's chinese room. |

The book that Searle is reading in this picture is a book written in English. Note that the only sentences on the page are sentences that you, as an English speaker, can understand. This book is one of countless volumes that together tell Searle what output (in the form of Chinese symbols) should be given in response to virtually any input (of Chinese symbols) that comes through the slot into the room. Each volume covers only a small percentage of the possible inputs. That's why there must be so many volumes. This particular volume tells what output to give in response to virtually any input of Chinese symbols that begins with the first two Chinese symbols written on the piece of paper.

Searle does not recognize any of the symbols. They are simply meaningless shapes to him. For all he knows, they may be nothing more than patterns for making wall-paper and not a language at all. As it turns out, the symbols do have meanings. They are Chinese symbols. More than that, they are questions in Chinese being asked by intelligent speakers.

The books function as a computer program. Each page gives instructions for how to manipulate symbols. The instructions at no point make any reference to the meaning of the symbols. (That is, nowhere will you find a sentence that gives the English translation of any of the Chinese symbols.) None of these books is anything like a Chinese-English dictionary. Instead, like a computer program itself, it instructs the reader how to manipulate the symbols based on their formal properties (their shape and position) not their meaning. If you see symbol "X" here, then write symbol "Y" there.

It is time to see the Chinese Room in action. Below is a Flash animation where a representation of John Searle is busy at work inside the Chinese Room. Click "Begin".

Let's imagine that the books in the Chinese Room prove to be an effective AI program that can pass the Turing Test in Chinese. In the animation you just viewed, the Chinese characters that were passed into the room asked the question: "What brings happiness?". And the Chinese characters that Searle wrote in response to that question are from the Tao Te Ching by Lao Tsu (although Searle doesn't know that) and the answer means,: "Be the stream of the universe." If the Chinese Room can pass the Turing Test, should we say that the room "understands" Chinese? "NO!" says Searle. If questions written in English were passed into the room, Searle would be able to read and understand them and write answers to them. But his relationship to the Chinese symbols is quite different. He could spend years, taking in thousands of pieces of paper with Chinese written on them, and he could write thousands of intelligent-sounding answers in Chinese, and yet at no point would he ever understand Chinese. Searle explains in his own words:

Suppose also that after a while I get so good at following the instructions for manipulating the Chinese symbols and the programmers get so good at writing the programs that from the external point of view—that is, from tile point of view of somebody outside the room in which I am locked—my answers to the questions are absolutely indistinguishable from those of native Chinese speakers. Nobody just looking at my answers can tell that I don’t speak a word of Chinese. Let us also suppose that my answers to the English questions are, as they no doubt would be, indistinguishable from those of other native English speakers, for the simple reason that I am a native English speaker. From the external point of view—from the point of view of someone reading my "answers"—the answers to the Chinese questions and the English questions are equally good. But in the Chinese case, unlike the English case, I produce the answers by manipulating uninterpreted formal symbols. As far as the Chinese is concerned, I simply behave like a computer; I perform computational operations on formally specified elements. For the purposes of the Chinese, I am simply an instantiation of the computer program.

Now the claims made by strong AI are that the programmed computer understands the stories and that the program in some sense explains human understanding. But we are now in a position to examine these claims in light of our thought experiment.

1. As regards the first claim, it seems to me quite obvious in the example that I do not understand a word of the Chinese stories. I have inputs and outputs that are indistinguishable from those of the native Chinese speaker, and I can have any formal program you like, but I still understand nothing. For the same reasons, Schank’s computer understands nothing of any stories, whether in Chinese, English, or whatever, since in the Chinese case the computer is me, and in cases where the computer is not me, the computer has nothing more than I have in the case where I understand nothing. ["Schank's computer" is a reference to a computer running an AI program written by Roger Schank called SAM (Script Applier Mechanism) which "reads" stories and answers questions about them.]

Searle believes that he has demonstrated that no computer program that manipulates symbols based solely on their formal "syntactic" properties (e.g., their shape and their position) can ever be said to understand a language . . even if it does pass The Turing Test. It is important to note that Searle is not saying that no machine can understand a language. He is a naturalist who believes that human beings are biological machines and that we understand a language. He is not even saying that no computer could understand a language. Again, humans are computers in the sense that certain operations of the human brain can properly be described as "computing," as "implementing functions." Searle is not insisting that humans do not compute and do not implement functions. He is insisting, however, that genuine thought and understand require something more than mere computation. In understanding a language we do not merely manipulate symbols based on their formal properties. We do something (he doesn't pretend to say what) in addition to manipulating symbols in virtue of which we actually understand the meaning of the symbols -- which the Chinese Room does not.

Responses to the Argument

It is probably safe to say that no argument in the philosophy of mind (or in any area dealing with the nature of thought and cognition) has generated the level of anger and the vitriolic attacks that the Chinese Room argument has. People do not merely accept or reject the argument: Often, they passionately embrace it or they belligerently mock it. The reason feelings run so high, I think, is that the argument has been very successful. In classrooms, when students with no background in the controversy first hear the argument, a majority (often a vast majority) immediately accept it. Many philosophers and scientists also accept the argument, although in that demographic the percentage of defenders is not nearly so large. Among those working in AI, cognitive science, and related fields, the feelings run strong because critics of the argument believe that it has had a negative impact on the field -- convincing people to abandon pausible and empirically powerful theories of the mind because of (what they consider to be) one dangerously misleading thought-experiment.

This is an important argument. Much discussed and much debated. The objective of this module is not to take sides. Instead, the goal is (1) to explain the structure of the argument (so as better to evaluate it), (2) to explain the structure of a few representative objections to the argument, and (3) to try to diagnose why there is such heated disagreement about whether the argument is or is not effective. In the end, we hope the reader will come away impressed by how deep the debate about the nature of the mind goes and how the Chinese Room argument might best be seen as a way to bring to light a person's fundamental assumptions about the nature of human thought and experience in much the same way that a Rorschach Test is supposed to reveal a person's deepest psychological traits.